An Inflection Point Beckons

An extract from the Introduction of our core text: ‘The Customering Method’, Routledge Press, a Division of Taylor & Francis (New York, London), November 2024.

There is no better example of a core strategic and fiscally critical function that is nonetheless characterized by widespread illiteracy than customer management. It is an arena of misadventure with consequences that extend beyond individual companies, to entire industries and the international economy.

Case in point, the global digital transformation market, of which customer programs are a considerable proportion, is projected to grow from US $2.71 trillion in 2024 to US $12.3 trillion by 2032 at a compound annual growth rate of 20.9%. Yet, the forecast failure rate of 87.5% underscores that deficiencies in customer management literacy and its governance are not solved by technology. Beyond the investment waste, the fiscal implications are manifold.

Both upstream and downstream of these transformation projects, the compounding effects of failed customer management are eye-watering. Accenture reported that customer switching between companies correlated to poor service “triggers” costs a whopping US $1.6 trillion per annum in the USA alone. Another study in 2021 went further, calculating that the annual global risk to sales from “bad experiences” is US $4.7 trillion, and there is significant corroboration as to both the pattern and proportions. For instance, 2018 research by NewVoiceMedia estimated that US $75 billion is lost to American businesses due to the failings of contact centers, which is but a single channel. In 2020, Statistica calculated that new spending on operational customer management amounted to US $323 billion, with over US $75 billion of that spent on customer loyalty programs despite scant evidence of correlated value.

Meanwhile, the Institute of Customer Service estimates that poor service results in additional needless customer interactions and costs UK businesses 11.4 billion per month.

The Profession that Wasn’t

The earliest detectable customer-based traditions date back to 3,000 BC, but it is

the 1950s that historians and economists credit for the Services Revolution. The first progression of macro-economic value since the Industrial Revolution, it was based on the primacy of the customer rather than purely on production efficiency. And so, in the shadow of World War Two, as society and its consumers sought easier lives, the foundations of what we now recognize as customer proximity first occurred.

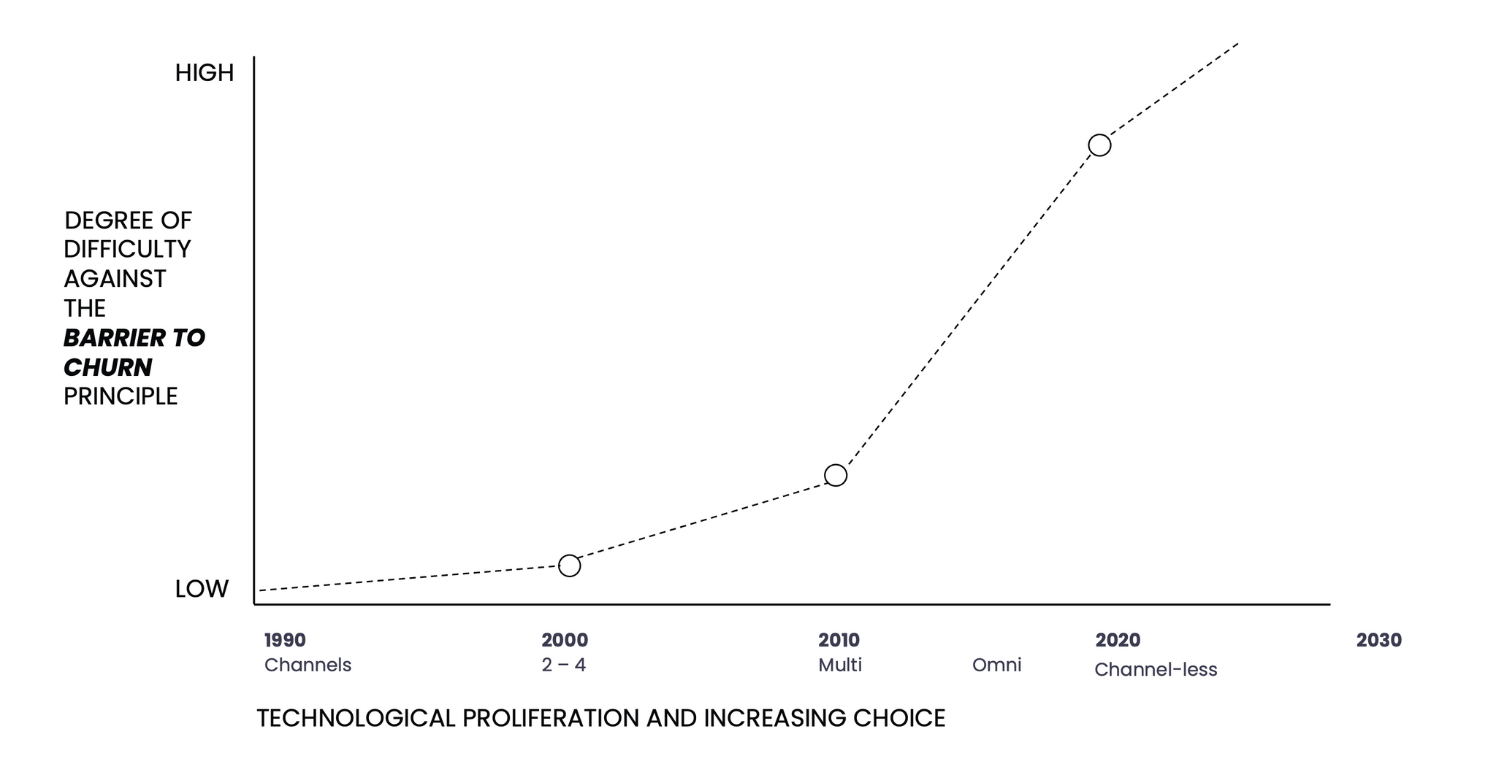

Yet the critical imperative for a true customer management profession, and a quality management system for the customer asset, did not emerge until the digital communications era began more than a half century later. As channel and device proliferation swelled, accelerating the effects of consumerism, the value drivers – and risks – to the customer franchise were unprecedented.

Just as the arrival of market-based economies at the start of the twentieth century had necessitated the development of the marketing method, this time, it was a method for the customer asset that become paramount.

And yet a strange thing happened – or didn’t happen, as it turns out.

Historically, when a field becomes material to both industrial success and to the apparent best interests of consumers, market and regulatory forces conspire to ensure its standardization, for both control and repeat effectiveness.

This has been true of legal services, architecture, the fields of medicine and engineering, aviation, accounting, construction, design, plumbing and electrical trades, maritime professions, nursing, teaching, and many more. Each is now characterized by recognizable industrial management practices, discipline specific language, aligned educational infrastructure, and well-enforced barriers to entry.

Yet this did not occur in customer management.

And so, when the digital era arrived, the field was not prepared as other vocations were. There was simply no large-scale procedural integrity resembling that of established professions that could allow the field to properly leverage the new capability. After such a long period of analog customer interaction, the world changed fundamentally and far too quickly for the customer management vocation to handle.

By 2007, there were one billion internet users, delivering critical mass for internet-based business models. The internet itself would go onto become the most powerful source of commoditization in history, significantly impacting brands and the behavioral loyalty of consumers. By 2012, cloud computing had become mainstream and bled into the rise of application development and mobile devices, which in turn spawned social media and extreme device proliferation.

The evolution continues, more latterly shifting to Web3.0, the Metaverse, and all manner of generative AI-based technologies. And so, in less than two decades, the world evolved from one or two, perhaps three, customer “channels” to manifold channels. In fact, by 2018 a study at Google found that a customer journey ranged between 20 and 500+ touchpoints.

It was this combination – the absence of mature management practice together with the rapid increase of complexity owing to technology, channel, touchpoint, journey, device proliferation, and associated consumer behaviors – that has proven to be a perfect storm for customer management

The Cost of CX Populism

As the bubble-like valuations of service-as-a-software companies erupted throughout the 2010s, product marketing teams were let loose with massive budgets. This saw novel technologies, with catchy sales slogans, flooding a market teeming with newly cashed-up but ill-informed clients. All were swept along by the hype, and without a north star governing model in sight, the customer experience (CX) movement was born.

Of course, there are many legitimate customer management leaders who, in the absence of an alternative, fall under the “CX” banner. While a diminutive minority, they are serious people who apply intellectual rigor to their work. These aside, however, the vast majority of the field is best characterized as populist.

Populism has become a central theme – and threat – to western societies and has been increasingly studied in economics, sociology and, of course, in political science. It is a phenomenon that is always detrimental to performance and that marginalizes expertise and knowledge (or facts) in general.

Specifically, populism:

- Holds simplistic views of both problems and solutions.

- Proposes simplistic policies which do not match the complexity of reality.

- Seeks to align with or secure the fealty of counterparts and sources of influence.

- Prefers loyalty (groupism) over expertise.

- Is serial in nature (prone to re-generate).

- Stimulates institutional and vocational decay.

- Presents as negative to economic and other measures of performance.

In a similar, if more entertaining, vein, American philosopher Harry Frankfurt’s 2005 book On Bullshit, defines the concept in societal terms and analyzes its applications in the context of communication. He draws the same directional conclusions as the Center for Economic Policy Research did, arguing that the rise of populism is dangerous because it accepts and enables a growing disregard of the truth, fact, or knowledge.

Undoubtedly confrontational for many, the paradigm of populism is nevertheless critical to understand in any examination of the CX movement.

The fledgling vocation, absent an industrialized method, was caught in a groundswell of trendy, post-modern business ideals (e.g., brands seeking to be more “human”), conditions in which the fever of populism was to flourish. The second paradigm to understand is the Solow Paradox.

The Solow Paradox

It is not unusual for technology companies, developing capabilities in the advancement of existing management disciplines, to lead the way in pioneering new approaches. Their business model often allows for well-funded research and development, both for their products and for industry-level expansion of knowledge. But many confuse the two.

Product development and positioning is ultimately a function of marketing. The clear commercial agenda is one of sales growth, which is of course entirely legitimate but is not a reliable basis for management theory. Distinguishing between pure commercial posturing and legitimate critical theory falls to the market, which in customering is a fraught task given the absence of industrial standards. Thus, we encounter a version of Solow’s Paradox:

“As more technology investment is applied, the effective productivity of workers goes down instead of up”.

Of course, there are plenty of examples where technology vendors have made meaningful contributions. Consider companies on the cutting edge of synthetic data in areas such as market diagnostics such as Evidenza, and in neuroeconomics – for example, Dr. Paul Zak’s digital platform, Immersion – and there is ample evidence of genuine leadership in the vendor community.

At the other end of the paradox, however, much vendor research is agenda-based, with the promotion of “findings” simply product marketing in disguise. Examples include the survey software category’s wildly successful scheme to create a vocation in its likeness, and similar parallels from the marketing technology (martech) sector, albeit from a more fragmented base

To generate unnatural demand for the inherently constrained utility of surveys, this category deploys a range of clever positioning concepts. While all are easily debunked, they have proven highly successful in an industry with populist traits. Chief among its many fables are the claims that feedback – not expertise – is foundational to industrial practice, and that self-reported data is reliable as behavioral insight. The creative injections of statistical analysis to invoke a false sense of scientific validation, the half-misappropriated idea of the “voice of the customer”, and even the re-branding of survey use as “experience management” – a concept entirely at odds with the available science – are other examples.

Lost within this rabbit warren, legitimate and contemporary customer management theory failed to become the norm, and absent this guardrail, customer interactions have been overtaken by a near-total focus on campaigns, offers, promotions, and wholesale or triggered sales activation. Due the influence of martech within digital teams, common use cases are invariably aimed at customers instead of the market, and in default sales mode. Yet customering is not (core) marketing: the purpose and methods are distinct, and those who are blind to this division use digital tools imprecisely, becoming toxic to the customer mission.

Procter & Gamble is among the companies most admired by marketing commentators and scholars, so it is no surprise that it was at the forefront of “digital marketing” as it took hold in the 2010s. However, it was also among the first to recognize much of its folly. In 2016, its chief brand officer, Marc Pritchard, said:

“In this digital age we’re producing thousands of new ads, posts, tweets, every week, every month, every year. We eventually concluded all we were doing was adding to the noise”.

A pity that the wider market did not prove so discerning. Instead, rampant sales activation and customer targeting has been responsible for the collapse of service, and customer trust with it. In fact, the dystopian business model of social media, first rationalized by advertising executives, has leached into daily commerce and is now so pernicious that law makers around the world are taking steps to protect our own customers – from us!

Built on populism and digital superstition, the conflation of marketing activation and customering is arguably among the greatest strategic errors of our time.

The CX Movement Has Failed

Considering the financial consequences of survey addiction as proxy for domain expertise, and of marketing-creep in place of service, the unavoidable conclusion is that the populist CX movement has been a calamity. Yet, while there may be suspicions at the executive table, this failure is not widely recognized in the movement itself – consistent with the sociology of populism.

To compound matters, we have witnessed the rise of an educational machinery distributing the dogmas of the movement, with “certifications” providing sham validation, followed by the usual range of debunked or non-critical concepts as modules attracting credits or “specialisms”. And so, while attendees become “certified” in one form or another, they are never educated. The fundamentals of legitimate customer management, the science, and economic underpinnings of its proper administration, remain foreign to them.

Enter Industrial Customering

The prevailing economics of customering at scale, attained through the nuanced and yet programmatic engagement of the individual as first envisioned in the 1950s and in later concepts like “mass customization”, remain largely – and inexcusably – unfulfilled.

Instead, as leaders stare down a progressively volatile world economy, they face needless uncertainty about how best to prioritize investment across the people, operations, and technology of their customer programs. The subsequent losses, in their trillions, mount up annually through avoidable customer attrition, cost of operations, realized risk, and failed digital transformation projects, all diminishing profit and shareholder value.

For the careers many, an inflection point beckons.

Join the next course and start learning

April 13th, 2026